Throughout the refugee crisis, European news media has focused on Syrians, often at the expense of other significant groups of migrants. Among these are Afghans seeking asylum in the EU, who made up 15% of total applicants in 2016. Afghans were also the second largest refugee group by nationality and were the biggest before the Syrian Civil War.

The fact of the matter is that the Afghan story is old. Major refugee migrations from Afghanistan have been occurring for the past forty years. Since the Saur Revolution of 1978, Afghans have mostly fled to Pakistan, with some asylum seekers (many of whom are Shi’a) going further to Iran, and an even smaller group heading to Europe. These routes will occasionally become busier, as they did when the Taliban ruled much of the country during the late 1990s.

Over the past two years, refugees have largely been fleeing a spike of violence that has accompanied a resurgent Taliban insurgency. Afghan refugees heading into Europe have been taking the Balkan Route, walking through Pakistan and Iran, taking a bus to the Turkish border, and then following the coast into Greece, usually with the goal of applying for asylum in Germany or Sweden.

The European Border and Coast Guard Agency (FRONTEX) has reported that between January and June 2017, Afghans have made 1,482 illegal border crossings, which makes them the second most numerous group behind Pakistanis fleeing the same conflict. These numbers are dramatically fewer than the first nine months of 2015, when Afghans were found to be responsible for 53,090 such crossings.

Furthermore, 178,200 Afghans sought asylum in European Union member states in 2015, and 183,000 Afghans refugees did the same in 2016, though the trend appears to be slowing in 2017. 12,428 Afghans applied for asylum in EU member states in the first quarter of 2017, which is 43% less than the last quarter of 2016, and 70% less than the same period last year. The decrease has been more general and is a result of aggressive Union measures to curb immigration.

In March 2016, EU leaders signed an infamous refugee deal with Turkey that allowed for deportation of undocumented immigrants to Turkey. The European Union now relocates “irregular migrants” (who do not apply or do not qualify for asylum) to Turkey as a buffer zone state, along with those who could have claimed protection in it as a “safe third country.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3mjRzxLcQUs

The deal also gives increased humanitarian assistance to refugees living in Turkey, promises a liberalisation of visa requirements for Turkish nationals, and increased resettlement efforts for Syrian refugees in the country. Effectively, though, the focus on Syrians means that other refugees, including Afghans, are simply sent to Turkey where they are reprocessed, and placed into new camps.

Later that same year, at a conference in Brussels, donors agreed to send $15.2 billion in assistance to Afghanistan, at around the same time that the EU and Afghanistan signed another agreement that allowed for the deportation of failed Afghan asylum seekers to Afghanistan.

Leaked memos show that the Afghan government was forced to accept 80,000 deported Afghans from the EU, in exchange for vital international assistance, a model that the European Union has also used in Niger and Ethiopia.

Germany is the most heavily criticised of EU member states for its Afghan repatriation policy, contending that parts of Afghanistan are safe to return asylum seekers to. The claim has been repeatedly disputed, particularly in Germany, but the policy’s continuation makes sense given that Germany continues to take in Syrian refugees, and needs to pretend it is being selective about who it lets in.

Perhaps the most dire consequences of these policies are to be found in Pakistan. The Afghan neighbour has been particularly empowered by tightening immigration restrictions in Europe, and responds by intensifying its own expulsions of Afghan refugees and their descendants. Islamabad has repeatedly pledged to throw out Afghan refugees in what Human Rights Watch has called “a campaign of abuses and threats,” which includes police abuse, extortion, arbitrary detention, and nocturnal raids.

This has been occurring at the same time that Pakistani politicians and oligarchs have been fomenting anti-Afghan sentiment, linking refugees to terrorism, drug trafficking, and Islamic extremism. The objective is to make life so miserable that the Afghans will leave, with Pakistan claiming that they have “left voluntarily,” even if they’ve lived in the country for decades.

Over 700,000 Afghan refugees returned to the country in 2016, mainly from Pakistan, but also Iran, and Europe. It is estimated that up to 2.5 million additional refugees will join them by mid-2018, raising serious questions about the country’s stability.

The rapid influx of such a large dependent population (which relative to Afghanistan’s population, is comparable to 50 million refugees entering the EU during the height of the crisis) is bound to exert undue pressure on infrastructure, state institutions, and both Afghan and Pakistani society as a whole. Given that leaders of European Union states have warned of exactly these problems when it comes to taking in large numbers of refugees, pushing them on Afghanistan seems hypocritical.

As far as the Pakistani government is concerned, this instability is the point, since it is using migration as a political weapon. An unstable Afghanistan ensures that Islamabad will be able to continue pursuing its interests there, rather than insure that the country grows stronger, becoming more potentially hostile to Pakistan, and building strategic partnerships with India.

It is difficult to know how the situation could change. The West remains preoccupied with instability in the northern Middle East, and the challenges posed by Islamic State, not South Asia, where the War on Terror, which triggered today’s refugee crisis, began. Until such a point that its instability threatens core American interests again, it’s unlikely that anyone will prioritize solving it.

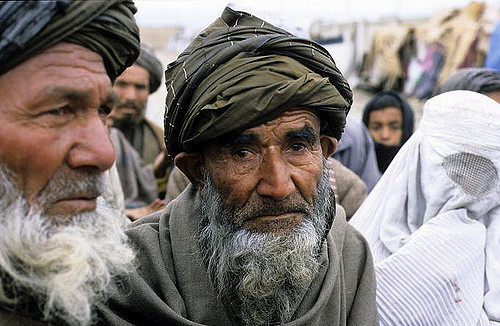

Photograph courtesy of United Nations Photo, and Marines. Published under a Creative Commons License.