The revelations of sexual misconduct by men dominating American media are having a profound impact on how people feel about their world. Last week, I stopped by the home of a senior citizen who needed help with something and heard, the second I opened the door, that M*A*S*H was playing on her television. But in place of nostalgia, I felt a surprising revulsion. While the show had never made me happy, exactly, because I used to watch it during the most unhappy years of my adolescence, its familiarity was a source of comfort.

Paradoxically, although M*A*S*H focuses on military personnel who invent new lives for themselves because they are so far away from their families, I have always identified it with home. A few bars of its famous theme, the sight of Corporal Klinger striding across the screen in a dress, even the sudden transition from laugh-track comedy to the somber drama of “Choppers!”: all had the power to return me to a place of safety and stability. Now, suddenly, that feeling had been turned inside out, providing me with a brief glimpse into a very different reality, one in which, for all of its politically progressive sentiments, M*A*S*H communicated a deep contempt for women.

I was so taken aback by this experience that I immediately shared it on Facebook. After noting that I was deeply indebted to the show for my “political convictions and sense of humor,” I described it as “not just sexist, but basically an endorsement of non-stop sexual harassment in the workplace. While that aspect of the show diminished over the years it was running — itself a development worth reflecting on, given the parallel backlash against the ERA and ‘Women’s Lib’ during that period — its noxious residue was impossible to wash off. Whoever decided that the liberation of men — the show is about resisting rules and regulations above all else — requires the abuse of women deserves a special place in hell.”

The minute I made this post, I started having second thoughts. Was this response to the show too influenced by present circumstances to be valid in the future? Had I oversimplified the show’s sexism, forgetting that it also made room for criticism of immature male behavior? Or was I neglecting the fact that the show takes place in a war zone, which is bound to have a profound effect on what sort of behavior is considered excessive?

Once responses from my friends on Facebook started coming in, however, it became clear to me that, even if I was being unfairly harsh in my characterization of M*A*S*H as a whole, I needed to revisit the show from the perspective of current events. I firmly believe that we are unlikely to change for the better unless we closely examine the influences that most shaped us as we were growing up. And I’d be hard pressed to come up with a television show that influenced me more than M*A*S*H did, even if I haven’t had much urge to watch it recently. The depth of the comments on my post suggested that a lot of other people felt similarly.

Over the course of its eleven seasons, M*A*S*H was the primary way millions of Americans processed the Vietnam War. Because the show was actually set during the Korean War instead, its audience was able to experience the tension between pacifism and patriotism in displaced form. As a child who had been absorbing the news coming from Indochina long before I knew what any of it actually meant, I instinctively knew that M*A*S*H concerned the world’s first truly televised war. But grown-ups could pretend otherwise long enough to open their hearts to sentiments that their political convictions would otherwise have blocked. This was especially important for the generation that had lived through World War II, which tended to recoil sharply against those young people who protested American foreign policy without having served in the military themselves.

While M*A*S*H’s irreverent humor had a distinct countercultural feel, it was back-dated just enough – exemplified by references to the early years of television comedy – to be acceptable to viewers on both sides of the generation gap. This made a lot of sense from a marketing standpoint: it was a top-rated program throughout its run. Unfortunately, though, this historical displacement also ensured that the impact of contemporaneous new social movements was muted. Explicit depiction of conflicts around race and gender could be avoided for the simple reason that they were anachronistic. To be sure, storylines during the latter years of the show thematized social issues more frequently. But the fact that M*A*S*H’s early seasons were still playing all the time throughout the 1970s and 1980s via syndicated reruns diminished the impact of this trend, because dedicated viewers were unable to get those episodes’ button-pushing slapstick comedy – today we would call it “politically incorrect” – out of their minds.

It’s interesting to look back at M*A*S*H now, because the historical distance that shapes contemporary responses to the show is mirrored by the geographic distance that is a crucial component of its storytelling. There’s a reason why the character of “Radar” was a central figure for the majority of its eleven-year run. Over and over again, he serves as the conduit for news that makes everyone’s mood shift rapidly, most famously when he comes into the operating room to announce that the unit’s first commander, Henry Blake, has perished on during his return journey to the United States. And, aside from the radio communications Radar oversees, there is at least one scene in most episodes when the sound of distant helicopters – announced with that famous cry of “Choppers!” – instantaneously ends whatever “normal” activities the show’s characters are pursuing. As these examples make clear, though, news from afar is almost always meaningful in ways that Americans back home would have found hard to comprehend.

It’s that sense of approaching trouble, whether waiting on the other end of the radio transmission or a few ridges over, that serves as the primary rationale for transgressive behavior. The sudden transitions from boredom to intense focus that characters must deal with creates a level of ambient anxiety that seems to retroactively legitimize a wide variety of rule-breaking behavior. M*A*S*H’s peculiar humor, particularly in its early seasons, derives from the sense that it serves this therapeutic function. It was clear to me even as a twelve-year-old that a lot of the situations from which the show’s comedy emerges would be hard for a decent person to laugh at with a clear conscience – superficially mean-spirited pranks abound – if the show weren’t repeatedly reminding us that they provide a desperately needed release for exhausted personnel who would might otherwise break under the pressure.

If we want to excuse M*A*S*H for repeatedly crossing the sort of lines that the #metoo movement has foregrounded, the easiest approach would be to convert space into time. The characters believe that their highly unusual circumstances justify transgressive behavior they would never have dreamed of condoning back home; we can argue that the context in which the show was produced, ideologically far away from our own, justifies its blatant sexism. In a comment on my Facebook post, Chuck Graham, a veteran newspaper critic here in Tucson, argued that “it would be much more productive to celebrate progress than to complain about a show whose popularity was very much a product of its time,” then followed up by adding that, “topical humor has a short shelf life.”

Building on Graham’s initial point, Christopher Foree cautioned against “contextless critique. A piece of art extracted from its context is an easy punching bag.” After noting that All in the Family could also “be considered in hindsight to have committed all sorts of narrative social crimes when pushed through the sieve of modern standards,” Foree referenced a science-fiction story about visitors from the planet Venus who land on Earth after human beings are no more and discover a time capsule. “In the capsule was an episode of The Flintstones, from which the aliens deduce that humanity was a brutal culture who hit people with clubs. . . when critiquing historical pieces of art one should be aware of one’s status as an alien.”

These cautionary words make a lot of sense to me. Even though “history is what hurts,” as cultural critic Frederic Jameson once declared, I always insist on placing texts in context. However, despite the fact that M*A*S*H derives from an era when sexual harassment was still likely to be considered a source of mirth – as it was for centuries, in plays, operas, and films – I’m reluctant to let the series off the hook. If I had only watched it to laugh, maybe its datedness in this regard wouldn’t bother me so much. But for me – and millions of other viewers, I’ll warrant – M*A*S*H was compelling precisely because the situations it presented could never be reduced to humor. The sense of impending danger it managed to sustain, through eleven years of cast changes, reminded us that that people in extreme circumstances will laugh because they want to cry. And, in identifying with them, viewers like me learned to take their own laughter seriously.

What I’m suggesting here is that M*A*S*H’s greatest strength – the recognition that laughter is rarely as light-hearted as it superficially seems – also underscores its greatest weakness. In making us reflect on our reasons for seeking humor in situations that aren’t really that funny, it opened up a space for critique, one which, assuming the stories about Alan Alda pushing to make the show less offensive are true, turned into self-critique. Looking at episodes from all of its eleven seasons in rapid succession, I did have a clear sense that the showrunners made a clear effort to compensate for their initial treatment of women. But as my friend Julie Anderson Reinhart noted, “The latter years of the show became more and more of a sermon, though, and could get tedious for that reason.”

That’s why I think we should pay special attention to the one aspect of M*A*S*H that persisted throughout its run. Responses to M*A*S*H varied widely, I’m sure, both during its original prime-time airing and decades of reruns. But I’d venture that a good number of the show’s most devoted viewers internalized its distinctive narrative structure, in which tedium was repeatedly interrupted by periods of intense stress, at a deep psychic level. I’m only just now realizing, as I write this, the degree to which I did so myself. Although I am not generally an anxious person, the show helped prepare me, from an extremely impressionable age, for a world in which the sudden intrusion of danger and fear was always lurking in the distance. While I’m sure that the threat of thermonuclear war also contributed to that sense of needing to be prepared for devastating news from afar, the fact that M*A*S*H concentrated on interruptions of regular routine that were more readily survivable made its rhythms easier to incorporate into my psyche and, I suspect, that of many other viewers.

Reflecting on this aspect of the show in light of the recent revelations of sexual misconduct, I’m forced to ask how much of the male behavior being exposed right now was undertaken with the mindset that stress made it easier to excuse. I don’t think it’s an accident that the majority have come from the realms of politics and entertainment, in which periods of sustained pressure are followed by interludes in which the desire for an outlet is strong. That’s why both of them are awash in drug and alcohol abuse, which also frequently leads to failures of judgment. Couple that dynamic with a culture in which transgressions by men – white men, anyway – have traditionally been excused more readily than those by women and the foundation was laid for pervasive sexual harassment and coercion.

And that is what I saw over and over again after I began watching episodes ofM*A*S*H for the first time in years. As troubling as my memories of the show had been, the concrete evidence of its mistreatment of women seemed even worse. This reinforced some of the harsher comments made in response to my original Facebook post. One local friend described being exposed to the show when visiting a close male acquaintance and his sister. “They both insist on watching reruns, and I hate it. I hate it exactly for the reasons you point out. I also find myself surprised they both comment on how sexist the show is, yet, insist on watching it. I tend to place myself outdoors while the show is on, it drives me that crazy.” Longtime San Francisco Bay Area music critic Gina Arnold pointed out that, “the movie M*A*S*H is horrible that way too…not just run of the mill sexist but demeaning and humiliating. I hate it.”

Susan Knight, who teaches journalism here at the University of Arizona, also acknowledged the importance of remembering the historical context in which M*A*S*H was produced, but suggested that its comedy was targeted primarily at men. “There’s a lot of humor that made women squirm, mixed in with truly funny stuffy and political wit, but then the stuff that just sort of cut us, diminished us. There’s sexual: FUNNY. Then there’s sexist: UNFUNNY.” Maria Coxon-Smith then asked, “Was it an accurate representation of how nurses in Korea were treated? Based on the issues still present in the military, I would think so. Whether it is funny is another issue.”

These helpful comments got me thinking about the place of realism in comedy. “Verisimilitude is a tricky concept,” I wrote in response to Coxon-Smith’s comment. “There is often humor to be found in the accurate rendering of life as it seems to be, rather than how we believe it SHOULD be. (Louis CK was a master at finding it). There’s always the risk, though, that this kind of ‘accuracy’ will just reinforce problems instead of pushing us towards fixing them.” When this happens in narratives that take place in a different era, the problem is compounded. Many Americans once found humor in the depiction of African-Americans as a people who are satisfied with simple pleasures, like eating watermelon. But no matter how accurate it might be to include such comedy in a story set during the early 1900s, it is hard to imagine anyone feeling comfortable doing so in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement.

As I have already noted, even though M*A*S*H evolved over the course of its run, the fact that it is one of the most successful syndicated shows of all time makes it impossible to forget its problematic beginnings. Corporal Klinger eventually stopped dressing like a woman in the hope of getting discharged for being mentally ill, but I’m willing to bet that just about everyone who watched the show regularly will picture him in a dress. And even though some of them remember the sensitive version of Hawkeye who bonded with head nurse Margaret Houlihan over the horrors they had witnessed together, they are much more likely to picture him with his buddy Trapper John, torturing the punctilious adulteress they reduce to a synecdoche, “Hot Lips.”

One thing I came to realize, after discussing M*A*S*H on Facebook, is that Margaret Houlihan, even more than Hawkeye Pierce, is the narrative center of the show. More than anyone, including the 4077’s commanding officers, she regulates the way in which characters interact with each other. As I noted in replying to a comment on my Facebook post, “it’s interesting, though, that Margaret gets positioned for years as someone who prevents ‘fun’ from happening. Despite her attractiveness, she is slotted into what a psychoanalyst might call the role of the castrating mother or, if you don’t want to go that far, the female authority figure who maintains order at the expense of liberty.”

But the evolution of her character complicates this picture – more successfully than in the case of Hawkeye, I’d argue – allowing even her role as antagonist in the show’s early years to be reconsidered. Matthew Runkel commented that, after acknowledging her affair with the execrable Major Frank Burns and later unsuccessful marriage, “she is a fundamentally sympathetic character because we understand what she wants and isn’t getting in her flawed relationships. We sense that her treatment of the nurses and the captains flows from resentment for the fun they are having and their free-and-easy lower standards that make that possible.”

For someone willing to think past the show’s ever-present laugh track, Houlihan could even be a locus of identification. After declaring that “most of the characters behaved like middle schoolers,” Anderson Reinhart replied to my comment about Houlihan’s status as an authority figure. “You say that the show was about resisting rules and regulations above all else, and obviously that was its primary theme. But, Margaret Houlihan was on the show throughout, and her character received development over those years. She suffered through lots of juvenile crap from her co-workers and labored on, and no one watching that show could ever have doubted her competency at her work. As a girl growing up watching her, I never thought of her in a bad light, if that makes any sense. I might laugh at this or that, but I never thought she was a bad nurse nor did the script make me think she didn’t deserve to have her rank. I suspect her character was a subliminal guide to many young women, offering them views into the multitude of issues that they would encounter on their career path.”

This excellent summary of Houlihan’s character suggests that, in spite of M*A*S*H obvious sexism, it was doing something more than just making audiences laugh at women. Certainly, a professional woman in the sort of situation where Houlihan finds herself would have needed to be strong and sometimes stern just to cope with the demands of her job. The realism Coxon-Smith referenced is perhaps easiest to perceive in the depiction of how Houlihan tries very hard to separate her public and private life, while Hawkeye and Trapper John try even harder to tear down the walls she has set up between them. Although they know that she is an excellent nurse and respect her work in the operating room, they still feel a compulsion to reveal that, underneath her perfectionism, she has the same flaws as everyone else.

The more I think about M*A*S*H, the more I wonder whether that isn’t the show’s most troubling aspect. Like many products of the counterculture, the early years of the series feature men trying very hard to convince women to be more liberated. But their investment in this project is clearly the product of self-interest. Maybe characters like Hawkeye really do believe that women will be happier if they act more like men. Goodness knows that plenty of men who supported women’s liberation in the 1970s felt that way. There is a difference, though, between how a person acts and how others act towards that person. So long as the women of the 4077 weren’t being treated with the same respect as men – and getting paid at the same rate, for that matter – the prospect of their sexual liberation was less appealing to them than it was to their male comrades.

As more and more men are accused of sexual harassment and the inevitable backlash against their “persecution” grows, we would do well to remember that many of the perpetrators were known publically for being supporters of feminism. For some of them, no doubt, this was purely for strategic reasons. But I’d bet that a greater number probably did believe in the liberation of women, Unfortunately, they were unable to perceive when their sincerity translated into self-interest. They learned to retroactively justify sexual misconduct because of the high-pressure professional lives they led, without comprehending that the women they harassed, abused, and assaulted were dealing with even higher pressure.

While there are numerous reasons for this ugly state of affairs, the influence of a show like M*A*S*H should not be underestimated. Because, once you convince someone that personal desires overlap with political ones, the potential for self-delusion expands enormously. The progressive movement needed men who would pursue the liberation of women in every respect, not just sexually. Even when we account for M*A*S*H’s historical context, it is abundantly clear that the show could have treated women a lot better. Some of its contemporaries, like Mary Tyler Moore, Alice and One Day at a Time did just that.

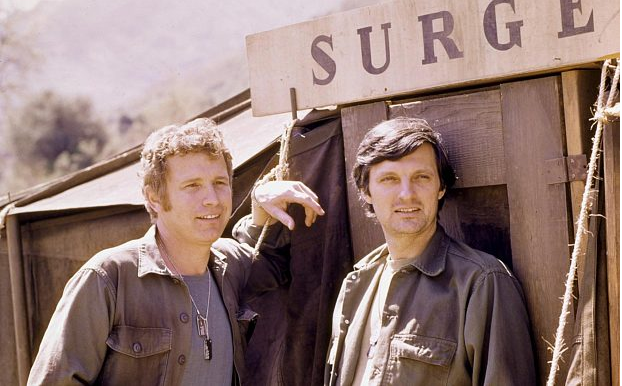

Image courtesy of CBS Television. All rights reserved.